![]()

-7-

CGI Programming

This chapter concentrates on the basics

of the Internet. By the time you reach the end of this chapter, you will be

comprehensibly conversant with the role of a web server, a web browser and

ASP.Net. You will also be in a position to appreciate the indispensability of

ASP.Net, in writing powerful business applications.

Understanding the samples

provided by Microsoft, is akin to viewing ASP from a height of 10000 miles.

At the outset, you are required

to create a file called a.cs in the sub-directory c:\inetpub\scripts. We will

explain the relevance of this subdirectory in due course of time.

a.cs

public class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("<b>hi");

}

}

The above is a short and sweet C#

program! Now, compile this program using the csc command, as in ‘csc a.cs’.

Then, run the executable and your

dos screen will simply display 'hi' with the bold tag in front of it.

To run this exe file from our

browser, we key in the following URL in the browser.

http://localhost/scripts/a.exe

This URL seems logical, since we

have placed the file a.exe in the scripts sub-directory. But, we do not seem to

get anything right the first time. This is evident from the following errors

that have been generated:

Output

CGI Error

The specified CGI application misbehaved by not returning a complete set of HTTP headers. The headers it did return are:

hi

The first line indicates that we

have written a CGI application. CGI stands for Common Gateway Interface. And we

have not adhered to the rules pertaining to a CGI application. The web browser

expects a complete set of headers, which we have not provided. Subsequently, we

see 'hi' displayed in bold.

Before moving into the details

about the rules, headers etc. of CGI programming, we shall send a header

across.

a.cs

public class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html");

System.Console.WriteLine("<b>hi");

}

}

We compiled the above program as

before and provided the same URL in the browser. It is preferable to load the

browser again and provide the URL. You could even click on the refresh icon

instead. Whichever method you follow, the same error is generated again.

In future, we will not repeat

these steps, but we do expect you to follow them, so that your output matches

with ours. Writing one more WriteLine function makes no difference at all.

a.cs

public class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html\n");

System.Console.WriteLine("<b>hi");

}

}

Output

hi

The mere inclusion of an 'enter',

represented by '\n', results in elimination of all the errors. We now see the

word 'hi' displayed in bold in our window. Before we explain as to why everything suddenly starts working

fine, let us make a small modification in the above program.

a.cs

public class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/plain\n");

System.Console.WriteLine("<b>hi");

}

}

Output

<b>hi

Now, it is time for us to

demystify this mystery.

The web or the HTTP protocol is

very simple to understand if you follow certain rules. When the browser

requests for a file from the web server, depending upon the extension given to

the file, the Web Server does one of the following:

• It picks the file up from its local hard disk and sends it across

OR

• It executes the executable file which has been requested for, from the disk which generates this file and sends it over.

In the case of a file with a .exe

extension, the server executes the file or program on its machine. This program

is not restricted to producing an HTML file only. It can create a file of any

type. If it were restricted to generating only HTML files, it would have made

the web very restrictive.

The contents of every file vary

depending on the file type. For example, an HTML file will contain tags; a .jpg

file will contain images, and so on. The browser must display the files in the

right format, on receiving them.

To inform the browser about the

file coming across, the exe file or program creates a header that signifies the

file type or the content type. A header is nothing but a word that is given

some value and which ends with a colon. Thus, the phrase 'Content-Type' is a

header since it ends in a colon, and the value assigned to it is 'text/plain'.

The rules of CGI state that all

headers must end with an Enter or '\n' symbol. This is so because a file can

have multiple headers. An 'enter' symbol, when placed by itself on a line, signifies

the end of all the headers. It also marks the start of the content. The Web

server is free to add its own headers to the list of headers generated by the

program. This composite data is then transferred to the browser.

Since the headers were not specified

in the first program, an error was generated. The presence of a Content-Type

header in a sense is mandatory for any

file that has to be transferred from the server to the browser.

The second error was reported

because we had omitted the 'enter' symbol all by itself, on a separate line, to

mark the end of all headers. Thus, more headers were expected from the server.

When this did not happen, the browser generated an error. The WriteLine

function adds an 'enter' symbol by default, but an additional \n is required

all by itself, to indicate an end to the Header values.

The browser uses the header named

Content-Type, to determine the type of data sent by the web server.

Accordingly, it displays the file in the right format.

The type text/html refers to a

text file containing html tags. Thus, 'hi' was displayed in bold. However, the

header value of text/plain informs the browser that plain text content is being

sent over, and hence, the tags are not parsed.

a.cs

class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

string s;

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html\n");

s=System.Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("PATH");

System.Console.WriteLine(s);

}

}

Output

C:\Program

Files\Microsoft.Net\FrameworkSDK\Bin\;C:\WINNT\Microsoft.NET\Framewor

k\v1.0.2204\;C:\WINNT\system32;C:\WINNT;C:\WINNT\System32\Wbem;C:\Program

Files\Microsoft SQL Server\80\Tools\BINN

An environmental variable is a

word stored by the operating system. In the world of Windows 2000, if we give

the command >set in the dos box, a

list containing a number of words with their corresponding values is displayed.

At the command prompt, if we give

the command >set aa=hi, it creates an environmental variable named 'aa' and

assigns it a value of 'hi' for the current dos session. On issuing the same set

command again, this recently created variable and its value, get displayed

along with the other environmental values.

The namespace System.Environment

has a static function called GetEnvironmentVariable. This function accepts an

environmental variable name and returns its value. In our program, we ask the

function to display the value of the environmental variable named PATH.

These variables are created and

maintained by the operating system. The web server too can ask the operating

system to create some variables, before it executes a program.

a.cs

class zzz {

public static void Main()

{

System.Collections.IDictionary i;

i=System.Environment.GetEnvironmentVariables();

System.Collections.IDictionaryEnumerator d;

d=i.GetEnumerator ();

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html\n");

System.Console.WriteLine(i.Count + "<br>");

while (d.MoveNext())

{

System.Console.WriteLine("{0}={1}<br>",d.Key,d.Value);

}

}

}

The above program shows 46 environmental

variables in the browser. An object named i of datatype IDictionary is defined.

It is initialized to the return value of the static function called

GetEnvironmentVariables.

This function returns an object

that contains all the environmental variables. We need a constant way of

retrieving data that is similar, but which has multiple occurrences. To do so,

the designers of the C# programming language have given us an enumeration

object which enables us to list the multiples values.

We use the GetEnumerator function

from the object 'i', and store its return value in the enumeration object named

'd'. The object named MoveNext iterates through the list of values. The object

contains two members called Key and Value. Basically, the format is Key=Value.

Thus, Key stands for the variable name and Value is the value contained in the

Key.

In the WriteLine function, {0}

displays the first parameter, {1} displays the second variable, and so on. The

Count member of IDictonary returns the count of the environmental variables.

Some of the variables are created

by the Operating System while it starts execution. The others are created by

the IIS WebServer. We searched the world over, but could not find a variable

named Query_String.

This program will be used in the

future. So we want you to make a copy of it and name it as b.exe: >copy a.exe b.exe

a.html

<html>

<body>

<form action=http://localhost/scripts/a.exe>

<input type = text name = aa>

<input type = text name = bb>

<input type = submit value = click>

</form>

</body>

</html>

The above HTML file is placed in

the wwwroot sub-directory and loaded as http://localhost/a.html. This file

shows two textboxes and a button labeled 'Click'. After entering the words 'hi'

and 'bye' in these textboxes, click on the button. You will be surprised to see

the browser displaying the same output as shown in the earlier program. But

observe that the count now displays the number 48, and the address bar now

contains the new URL http://localhost/scripts/a.exe?aa=hi&bb=bye. One of

the newly added name-value pair is :

QUERY_STRING=aa=hi&bb=bye

On receiving the new URL from the

web browser, the server simply creates an environmental variable called

QUERY_STRING and initializes it with the values that are contained in the URL after

the ? symbol. Thereafter, it calls the program named a.exe given in the URL,

from the relevant directory.

The program on the server can

easily identify as to what the user has entered in the textboxes. It simply has

to use the Request class or parse the QUERY_STRING variable.

Cookies

Before taking a leap into this

section, we would like you to set a few options in your browser. First, go to

menu option 'Tools' and select the last option named 'Internet Options'. Select

the Security tab. Ensure that you have selected the ‘Local Intranet’ option and

click on Custom level. Scroll down the list box until you see the heading

'Cookies'. For both the sub options, select the 'Prompt' radio button. The

default is 'Enable'. Restart the browser after making the changes. Now, run the

program given below in your browser.

a.cs

class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html\nSet-Cookie:aa=vijay\n");

System.Console.WriteLine("hi");

}

}

To our utter surprise, we see a

dialog box titled 'Security Alert', asking us whether we would be interested in

saving a temporary file sent by the WebServer on our hard disk. This file is

termed as cookie.

Firstly, we click on the button

labeled 'More Info'. This extends the dialog box to give us more information

about the cookie. Notice that the

cookie is named as aa, and along with other information, it reveals that the

data in this cookie is vijay.

Click on 'yes' and you will see

'hi' in the browser. Subsequently, if you run b.exe in the browser, it will

display all our environmental variables as before. But now, an additional

environmental variable called HTTP_COOKIE is created with the value of

aa=vijay.

Before we go further, let us

first run the following ASP program in the browser using:

http://localhost/a.aspx?aa=hi&bb=bye

a.aspx

<html>

<%@ language="C#" %>

<body>

<%

Request.SaveAs("c:\\z.txt",true);

%>

</body>

</html>

z.txt

GET /a.aspx?aa=hi&bb=bye HTTP/1.1

Connection: Keep-Alive

Accept: image/gif, image/x-xbitmap, image/jpeg, image/pjpeg, application/vnd.ms-powerpoint, application/vnd.ms-excel, application/msword, */*

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept-Language: en-us

Host: localhost

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; COM+ 1.0.2204)

For the ones who came in late,

whenever we click on a button of type submit, a new URL is generated. The Web

browser calls on the WebServer again, and sends it a packet of data.

To view the contents of this

packet, the Request property is used. This property returns an HttpRequest

object. SaveAs is one of the functions in the object that takes two parameters:

• The filename in which it can save the request.

• A bool value of true or false. If the value is true, the header is also saved in the file.

Any packet sent by the browser

has two parts to it. It starts with the word GET, followed by the URL that is

to be fetched. The name of the computer, localhost, is removed from the URL, as

the browser connects to it. Following it is the data, as entered in the browser

window.

All this is part of the HTTP

protocol. The protocol states that the URL is to be followed by the http

version number.

When the web server sends data to

the browser, the packet starts with the headers, followed by a blank line, and

finally, followed by the rest of the HTML file. On the other hand, in the

packet sent from the browser, the URL is stated first, followed by the data and

finally, there are the headers. This is exactly the reverse of what happens in

the case of the web server!

At first, we run the executable

from the browser as http://localhost/scripts/a.exe and accept the cookie.

Thereafter, the file a.aspx is copied from c:\inetpub\wwwroot to

c:\inetpub\scripts and loaded as http://localhost/scripts/a.aspx. The file

named z.txt, is shown below.

z.txt

GET /scripts/a.aspx HTTP/1.1

Connection: Keep-Alive

Accept: image/gif, image/x-xbitmap, image/jpeg, image/pjpeg, application/vnd.ms-powerpoint, application/vnd.ms-excel, application/msword, */*

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept-Language: en-us

Cookie: aa=vijay

Host: localhost

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; COM+ 1.0.2204)

A cookie has a header named Set-Cookie,

which is sent by the server to the client. A point to be noted here is that the

server initiates a cookie, and not a client.

There is a program that runs on

the server, which directs the server to send a cookie, which has a specific

name and value. When the client browser, which could be Netscape, IE or any

other browser, sees a header named Set-Cookie, it checks for the cookie-option

values. If the prompt is set on, the browser will display a message, thereby,

requesting for permission to accept or reject the cookie.

If the reply is 'yes', then

whenever the client connects to the server, it will contain a header named

Cookie, which it will send to the server. Thus, we see the header Cookie:

aa=vijay in the file z.txt. The text 'Set-' is removed from the Header.

Thus, a cookie is basically a

header-value that is sent by the server, and which is returned by the browser.

These cookies remain in existence

only until the browser is alive. If you close the current copy of the browser

and reload it again with the file a.aspx, the cookie header will not be seen.

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html\nSet-Cookie:aa=vijay; path=/aa\n");

A cookie header, along with the

name-value, has a path that decides on the sub-directories that the cookie can

be sent to. On running a.exe from the scripts sub-directory, the path parameter

in the cookie dialog box shows the path as /scripts/.

Therefore, if you load a.aspx

from the inetpub\wwwroot sub-directory, it will not show the Cookie: header in

the file z.txt. This is because the browser not only stores the domain name or

name of the computer, but also the URL or sub-directories that the cookie

should be sent to. As the path is /scripts, the browser will only send a

Cookie: header to the URLs that access files in the /scripts sub-directory.

Now, we shall see how our cookies

can be made eternal, so that they never say die.

a.cs

class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html\nSet-Cookie:aa=Vijay; expires=Tuesday, 03-04-2002 12:12:23\n ");

System.Console.WriteLine("hi");

}

}

After leaving a space after the

semicolon, we have simply added the word 'expires'. This is initialized to a

date in a certain format, followed by time in hours, minutes and seconds. The

cookie dialog box( that had earlier displayed the Expires as 'end of session),

now displays a specific date.

Upto this date, each time we

connect to a certain path on the server called localhost, the browser will send

this cookie. The earlier cookies were termed as 'session cookies', since their

life span extended only till the end of the session. The cookies where

'expires' is mentioned, are called 'non session cookies'. If we disable the

cookies, the browser does not send the Cookie: header to the server.

Let us now understand the

Response and Request objects in ASP.Net, which are introduced when they are

derived from the Page class.

The Request Object

The property Request in the Page

class, is of type HttpRequest, and it contains code that handles the data sent

by the browser.

This makes it easier for our aspx

program to parse the output sent to us by the browser.

a.aspx

<html>

<%@ language="C#" %>

<body>

<%

String[] s = Request.AcceptTypes;

Response.Write(s.Length.ToString());

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

Response.Write(s[i] + "<br>");

}

%>

</body>

</html>

Output

8image/gif

image/x-xbitmap

image/jpeg

image/pjpeg

application/vnd.ms-powerpoint

application/vnd.ms-excel

application/msword

*/*

The web server sends the header

Content-Type to signify the type of content that is to follow. The type given

after Content-Type is also called the 'MIME type'. The client, i.e. the browser

too sends across the types it supports, by using a header called Accept.

This header is sent as follows:

Accept: image/gif, image/x-xbitmap, image/jpeg, image/pjpeg, application/vnd.ms-powerpoint, application/vnd.ms-excel, application/msword, */*

Thus, the MIME type starts with

the name of a family, such as image, text, application etc. This is followed by

a slash /, after which we specify the different types within the family. The

symbol */* indicates that the browser supports all MIME types.

The Request object has a property

called AccessTypes, which returns an array of strings. We simply display them

using a 'for' loop. The Length property gives us the number of members present

in the array.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.ApplicationPath);

%>

Output

/

The property ApplicationPath

displays the virtual path to the currently running server application. Even if

you copy the file in the scripts sub-directory and change the URL to

http://localhost/scripts/a.aspx, the result will still be a slash i.e. /.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpBrowserCapabilities b = Request.Browser;

Response.Write("Type = " + b.Type + "<br>");

Response.Write("Name = " + b.Browser + "<br>");

Response.Write("Version = " + b.Version + "<br>");

Response.Write("Major Version = " + b.MajorVersion + "<br>");

Response.Write("Minor Version = " + b.MinorVersion + "<br>");

Response.Write("Platform = " + b.Platform + "<br>");

Response.Write("Is Beta = " + b.Beta + "<br>");

Response.Write("Is Crawler = " + b.Crawler + "<br>");

Response.Write("Is AOL = " + b.AOL + "<br>");

Response.Write("Is Win16 = " + b.Win16 + "<br>");

Response.Write("Is Win32 = " + b.Win32 + "<br>");

Response.Write("Supports Frames = " + b.Frames + "<br>");

Response.Write("Supports Tables = " + b.Tables + "<br>");

Response.Write("Supports Cookies = " + b.Cookies + "<br>");

Response.Write("Supports VB Script = " + b.VBScript + "<br>");

Response.Write("Supports Java Script = " + b.JavaScript + "<br>");

Response.Write("Supports Java Applets = " + b.JavaApplets + "<br>");

Response.Write("Supports ActiveX Controls = " + b.ActiveXControls + "<br>");

Response.Write("CDF = " + b.CDF + "<br>");

%>

Output

Type = IE5

Name = IE

Version = 5.5

Major Version = 5

Minor Version = 0.5

Platform = WinNT

Is Beta = False

Is Crawler = False

Is AOL = False

Is Win16 = False

Is Win32 = True

Supports Frames = True

Supports Tables = True

Supports Cookies = True

Supports VB Script = True

Supports Java Script = True

Supports Java Applets = True

Supports ActiveX Controls = True

CDF = False

The Browser property in the

Request Object returns an object of type HttpBrowserCapabilities. Thus, an

object b of this type is created and it stores the return value of this

property. We then display all the members of this class, which consist of the features

of the browser that just connected to the server.

Depending upon the values that

are supported and returned by the browser, the aspx file can be made generic,

to enable it to handle the differences among browsers.

The type member returns the name of

the browser along with its version number, whereas, the Browser property

returns only the name. The version number is displayed as 5.5. We can even

display the major and the minor version numbers separately. It is mandatory to

have the Version of the Explorer greater than 5.0, otherwise, the .Net

framework does not reveal the right values.

The property named 'Platform'

informs us about the Operating System that the browser is running on. If the

browser is currently running on Windows 2000, the platform property still

displays the value as WinNT. Our version of IE is the final copy, and not the

beta version, hence, the value of the property named beta is shown as false.

Search engines crawl all over,

looking for websites. Since ours is a simple browser, the property named

IsCrawler is shown as false. America Online is the largest on-line service in

the world and it has its own branded browser. Since we are using IE from

Microsoft, the property named AOL has a value of false.

Earlier, Microsoft had a 16 bit

operating system called Windows 3.1. As we are presently running their 32 bit

Operating system, the property Win16 is false, while the property Win32 is

true. An HTML page is divided into smaller parts by frames. Today, all browsers

support frames. Thus, the Frames property has a value of true.

Earlier some browsers could not

display tables. Thus, the tables property was introduced in the object. Today,

all the browsers fully support tables. However, not every browser can run Java

applets within the browser. In our case, since IE can do so, the JavaApplets

property is true.

All browsers support cookies,

since it is a standard created by Netscape. We have two main client side

scripting languages, VBScript from Microsoft and Javascript from Netscape. Since

our browser supports both, their properties are true. And since ActiveX was

invented by Microsoft, this property also has a value of true.

Finally, if we want to webcast

something, there is a new format called Channel Definition Format or CDF, which

has to be used. For some reason, IE does not support it.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Encoding e = Request.ContentEncoding;

Response.Write(e.EncodingName); %>

Output

Unicode (UTF-8)

The Request.ContentEncoding

property returns an Encoding object. This object also has a large number of

properties and methods. One of them is called EncodingName, which reveals the

Character Set that the browser uses to transfer data to and fro.

a.cs

class zzz

{

public static void Main()

{

System.Console.WriteLine("Content-Type:text/html");

System.Console.WriteLine("Set-Cookie:aa=vijay0; expires=Tuesday, 09-09-2001 12:12:23");

System.Console.WriteLine("Set-Cookie:a1=vijay1; expires=Tuesday, 09-09-2001 12:12:23");

System.Console.WriteLine("Set-Cookie:a2=vijay2; expires=Wednesday, 10-10-2001 12:12:23\n");

System.Console.WriteLine("hi");

}

}

We first loaded the following C#

executable from the script sub-directory:

http://localhost/scripts/a.exe

This sets three cookies for the

browser session, which is currently active.

Then, we ran the aspx program (as

given below) from the scripts sub-directory, using:

http://localhost/scripts/a.aspx

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookieCollection cc;

cc = Request.Cookies;

Response.Write(cc.Count.ToString() + "<br>");

for (int i = 0; i < cc.Count; i++)

{

HttpCookie c = cc[i];

Response.Write(c.Name + "=" + c.Value + "<br>");

}

%>

Output

4

aa=vijay0

a1=vijay1

a2=vijay2

ASP.NET_SessionId=wnyumy5544u3tj55tdrp0u45

Request.Cookies returns an HttpCookieCollection

object that is stored in the object cc. This object named cc has a member named

count, which returns a count of the number of cookies present in the

collection. We have 4 cookies, and hence, the 'for' loop is repeated four

times.

HttpCookieCollection has an

indexer that allows access to the individual cookies. Thus, cc[0] refers to the

first HttpCookie object, and so on. The HttpCookie class in turn, has two

important members, i.e. Name and Value, which display the name of the cookie and

its value, respectively.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookieCollection cc;

cc = Request.Cookies;

HttpCookie c = cc["a1"];

Response.Write(c.Name + "=" + c.Value + "<br>");

%>

Output

a1=vijay1

The indexer in the HttpCookieCollection

object can also accept a string, which is the name of the cookie. It returns a

cookie object that represents that cookie. The Value member will display the

value contained in the cookie. This will retrieve only a single cookie.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookieCollection cc;

HttpCookie c;

cc = Request.Cookies;

String[] s = cc.AllKeys;

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

Response.Write(s[i] + "<br>");

}

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

c = cc[s[i]];

Response.Write("Cookie: " + c.Name + " ");

Response.Write("Expires: " +c.Expires + " ");

Response.Write ("Secure:" + c.Secure + " ");

String[] s1 = c.Values.AllKeys;

for (int j = 0; j < s1.Length; j++)

{

Response.Write("Value" + j + ": " + s1[j] + "<br>");

}

}

%>

Output

aa

a1

a2

langpref

ASP.NET_SessionId

Cookie: aa Expires: 1/1/0001

12:00:00 AM Secure:False Value0:

Cookie: a1 Expires: 1/1/0001

12:00:00 AM Secure:False Value0:

Cookie: a2 Expires: 1/1/0001

12:00:00 AM Secure:False Value0:

Cookie: langpref Expires: 1/1/0001

12:00:00 AM Secure:False Value0:

Cookie: ASP.NET_SessionId

Expires: 1/1/0001 12:00:00 AM Secure:False Value0:

Just as there are many ways to

skin a cat, there are also numerous ways of displaying a cookie. The

HttpCookiecollection class has a member called AllKeys that returns an array of

strings, which represent the names of the cookies or its keys. Thus, in one

stroke, we can figure out all the names of the cookies.

After displaying the individual

names of the Cookie in the 'for' loop, the same name is used in the indexer, to

access the individual cookie object. The 'expires' property inexplicably, does

not display the correct date and time. Further, the Values object must be used

in place of the Value property, because a cookie can have multiple values.

Thus, c.Values.AllKeys returns an array of strings. Since in the present case,

every cookie has only a single value, the 'for' loop executes only once.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.FilePath);

%>

Output

/a.aspx

The property named FilePath

returns the virtual path of the request. The output reflected is /aspx, because we are loading this file from

the wwwroot sub-directory. If you run the file from the scripts sub-directory,

the output will display /scripts/a.aspx

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

NameValueCollection c;

c=Request.Headers;

String[] s = c.AllKeys;

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

Response.Write("Key: " + s[i] + " ");

String[] s1=c.GetValues(s[i]);

for (int j = 0; j<s1.Length; j++)

{

Response.Write("Value " + j + ": " + s1[j] + "<br>");

}

}

%>

Output

Key: Connection Value 0: Keep-Alive

Key: Accept Value 0: */*

Key: Accept-Encoding Value 0: gzip, deflate

Key: Accept-Language Value 0: en-us

Key: Cookie Value 0: langpref=C#; ASP.NET_SessionId=abksbkrxdgjmmj45hasiffzx

Key: Host Value 0: localhost

Key: User-Agent Value 0: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914)

The Headers property returns a

NameValueCollection object that represents all the headers. The rules for

handling headers are common for all headers. The rules are all in the form of

name=value. The object c has an AllKeys property, which returns a list of keys.

As before, we use a loop and call the function GetValues, which returns an

array of strings when it is supplied with a key value. Most of the time, we

only have a single value. Hence, our array s1 has a length of one.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

NameValueCollection c;

c=Request.Headers;

String[] s = c.AllKeys;

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

Response.Write("Key: " + c[i] + " ");

String s1=c.Get(s[i]);

String s2=c.Get(i);

Response.Write("Value " + s1 + " " + s2 + "<br>");

}

%>

Output

Key: Keep-Alive Value Keep-Alive Keep-Alive

Key: */* Value */* */*

Key: gzip, deflate Value gzip, deflate gzip, deflate

Key: en-us Value en-us en-us

Key: langpref=C#; ASP.NET_SessionId=abksbkrxdgjmmj45hasiffzx Value langpref=C#; ASP.NET_SessionId=abksbkrxdgjmmj45hasiffzx langpref=C#; ASP.NET_SessionId=abksbkrxdgjmmj45hasiffzx

Key: localhost Value localhost localhost

Key: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914) Value Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914) Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914)

The output is the same as before,

but it is easier to comprehend now, since a function called Get is used, which

returns a single string value. Every value is displayed twice, because we have

used both the forms of the Get function, i.e. passing it a string and then, passing

it a number. It is the browser that sends these headers. You can easily verify

this by inspecting the file z.txt, which has been created earlier.

Let us first create a simple aspx

file that merely writes out the value of a property called HttpMethod.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.HttpMethod);

%>

a.html

<html>

<body>

<form action=http://localhost/a.aspx METHOD=GET>

<input type = text name = aa>

<input type = text name = bb>

<input type = submit value = click>

</form>

</body>

</html>

In the above HTML file, we have

added an attribute called 'METHOD=GET' to the form tag. When we click on the

'click' button, browser screen loads on, with the address containing the action

value of http://localhost/a.aspx, followed by the ? symbol and the name value

pairs. The word GET is also displayed in the browser window.

Now, we make a small modification

in the HTML file. We replace the words GET with POST. When we load the file,

everything remains the same. When we click on the button, the browser now

displays POST. Further, the URL contained in the address bar does not contain

either the question mark or the name-value pairs.

The difference between a GET and

POST method is that, in a POST, the data is transmitted as a separate packet,

whereas, in a GET, it is sent as part of the URL. In Get, there is a limit to

the amount of data that can be sent as part of the URL. Passwords and other

important information must always be sent using the POST method and not the GET

method.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.IsAuthenticated + "<br>");

Response.Write(Request.IsSecureConnection + "<br>");

%>

Output

False

False

We have neither authenticated our

connection, nor have we been using a secure connection. A secure connection begins

with 'https', instead of 'http'.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.Path);

%>

Output

/a.aspx

This property displays the

virtual path of the current request.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.PhysicalApplicationPath);

%>

Output

c:\inetpub\wwwroot\

The Web Server can be installed

anywhere on the hard disk. The default directory selected by IIS is

C:\inetpub\wwwroot. As we have used the defaults, the property PhysicalApplicationPath

reveals the same path. The PhysicalApplicationPath is called the home directory

or the root directory of IIS. Whenever a file is to be referred to on the hard

disk, this value is added to the filename. Further, the slash symbol /, which

represents the virtual directory, finally gets converted into this physical

path, while it is locating or sending files to the browser.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.PhysicalPath);

%>

Output

c:\inetpub\wwwroot\a.aspx

In this program, we go a step

further and ask for the full path name or the physical filename of our aspx

file.

For the next program, we write

the following URL in the browser:

http://localhost/a.aspx?aa=hi&bb=bye&aa=no

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

NameValueCollection c=Request.QueryString;

String[] s = c.AllKeys;

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

Response.Write(s[i] + " ");

String[] s1 = c.GetValues(s[i]);

for (int j = 0; j < s1.Length; j++)

{

Response.Write("Value " + j + ": " + s1[j] + " ");

}

Response.Write("<br>");

}

%>

Output

aa Value 0: hi Value 1: no

bb Value 0: bye

The QueryString property returns a NameValueCollection. The

AllKeys property of this object returns only two keys, which is because we have

repeated the parameter name aa twice. We are permitted to repeat names in HTML.

The 'for' loop is repeated twice

for the two keys. The GetValues function returns an array consisting of two

members for aa, which is because it contains two values i.e. 'hi' and 'no'. The

second 'for' loop displays these values.

Working with ASP+ is a pleasure,

since there is an inbuilt code for handling multiple values.

If we run the earlier HTML file

with the method as Post, we shall not receive any output, because the environmental

variable QueryString holds values only with the Get method.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.RawUrl);

%>

Output

/a.aspx

The RawUrl displays the URL in

its most primitive form.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

NameValueCollection c;

c=Request.ServerVariables;

String [] s = c.AllKeys;

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

Response.Write(s[i] + "=");

String [] s1 =c.GetValues(s[i]);

for (int j = 0; j < s1.Length; j++)

{

Response.Write(s1[j] + " ");

}

Response.Write("<br>");

}

%>

Output

ALL_HTTP=HTTP_CONNECTION:Keep-Alive HTTP_ACCEPT:*/* HTTP_ACCEPT_ENCODING:gzip, deflate HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE:en-us HTTP_COOKIE:langpref=C#; ASP.NET_SessionId=abksbkrxdgjmmj45hasiffzx HTTP_HOST:localhost HTTP_USER_AGENT:Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914)

ALL_RAW=Connection: Keep-Alive Accept: */* Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate Accept-Language: en-us Cookie: langpref=C#; ASP.NET_SessionId=abksbkrxdgjmmj45hasiffzx Host: localhost User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914)

APPL_MD_PATH=/LM/W3SVC/1/ROOT

APPL_PHYSICAL_PATH=c:\inetpub\wwwroot\

CONTENT_LENGTH=0

CONTENT_TYPE=

GATEWAY_INTERFACE=CGI/1.1

HTTPS=off

INSTANCE_ID=1

INSTANCE_META_PATH=/LM/W3SVC/1

LOCAL_ADDR=127.0.0.1

PATH_INFO=/a.aspx

PATH_TRANSLATED=c:\inetpub\wwwroot\a.aspx

QUERY_STRING=

REMOTE_ADDR=127.0.0.1

REMOTE_HOST=127.0.0.1

REQUEST_METHOD=GET

SCRIPT_NAME=/a.aspx

SERVER_NAME=localhost

SERVER_PORT=80

SERVER_PORT_SECURE=0

SERVER_PROTOCOL=HTTP/1.1

SERVER_SOFTWARE=Microsoft-IIS/5.0

URL=/a.aspx

HTTP_CONNECTION=Keep-Alive

HTTP_ACCEPT=*/*

HTTP_ACCEPT_ENCODING=gzip, deflate

HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE=en-us

HTTP_COOKIE=langpref=C#; ASP.NET_SessionId=abksbkrxdgjmmj45hasiffzx

HTTP_HOST=localhost

HTTP_USER_AGENT=Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914)

The server creates a large number

of variables. They are too numerous to be displayed. Here, we are only

displaying the variables that have values.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Uri o = Request.Url;

Response.Write("URL Port: " + o.Port + "<br>");

Response.Write("URL Protocol: " + o.Scheme + "<br>");

Response.Write("URL Host: " + o.Host + "<br>");

Response.Write("URL PathAndQuery: " + o.PathAndQuery + "<br>");

Response.Write("URL Query: " + o.Query + "<br>");

%>

Output

URL Port: 80

URL Protocol: http

URL Host: localhost

URL PathAndQuery: /a.aspx?aa=hi&bb=bye

URL Query: ?aa=hi&bb=bye

The Url property in the Request object,

returns an HttpUrl object. This object has many properties, which break up the

URL into different components. The port number is related to the protocol used.

Every packet on the Internet is

tagged with a number that signifies the protocol that carries it. For e.g., the

http protocol has the port no. 80, E-Mail read is 25, FTP is 21, etc. Thus, the Port shows a value of 80 because

the URL that has been entered, starts with the syntax http:. Similarly, the protocol

used is http.

Host is the name of our computer.

PathAndQuery contains the name of the requested file along with the

querystring.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.UserAgent);

%>

Output

Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.5; Windows NT 5.0; .NET CLR 1.0.2914)

A user agent is another name for

the browser. The internal name for Netscape was Mozilla. So, IE initially

referred to itself by the same name. Many of the websites performed a check on

the browser that was requesting for the file. If it matched IE, the page was not

sent across. However, today it is IE that has eventually won the browser war.

We shall talk about it later, since it is too long an account to be related to

you right away.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Request.UserHostAddress);

%>

Output

127.0.0.1

Every computer on the Internet is

known by a number, which is technically called an IP address. It is of a long

data type. This implies that it consists 4 numbers, each ranging from 0 to 255.

These numbers are separated by dots. This format is known as the decimal dotted

notation.

As every machine is known as

localhost and it is given an IP address 127.0.0.1. Thus, when we write

localhost in the IE address bar, it gets converted to 127.0.0.1.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

String[] s = Request.UserLanguages;

for (int i = 0; i < s.Length; i++)

{

Response.Write(s[i] + "<br>");

}

%>

Output

en-us

The property UserLanguages

returns the languages that the browser supports. In our case, the browser

supports the English language, or more precisely, 'en-us', which stands

for American English and not for

British English.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

String s = Request.MapPath("/quickstart");

Response.Write(s);

%>

Output

C:\Program Files\Microsoft.Net\FrameworkSDK\Samples\QuickStart

When the .Net sdk installs

itself, it creates virtual directories in IIS. Thus, when we write

http://localhost/quickstart, it converts the virtual directory named quickstart

to the path displayed above. The MapPath function in the Request Object,

converts a virtual directory to an absolute path on your hard disk.

The Response Object

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Response.BufferOutput.ToString());

%>

Output

True

The first property we delve upon

in the HttpResponse class is BufferOutput. This property returns a logical

value of either a True or False. In doing so, it keeps us posted on whether the output sent to the browser

will be buffered or not.

While using the Write function

from the Response class, the data doesn't have to be sent to the browser at

once, as this will result in too many small packets being sent across.

Therefore, on grounds of efficiency, the text is collected and sent only when a

critical mass is reached. By default, the buffering option is on. Unless you

are equipped with a valid reason, you should not turn it off.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.ContentType = "Text/plain";

Response.Write("<b>hi");

%>

Output

<b> hi

The web server sends a series of headers

to the browser. It then follows it up with the actual content. As explained to

you earlier, the most important header is Content-Type. If we avoid creating

this header in our file, IIS defaults to the type value as text/html.

Here, we have changed the

Content-Type property in Response to text/plain. Thus, the <b> tag is

treated as text and not a HTML tag.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write(Response.IsClientConnected.ToString());

%>

Output

True

This function simply returns true

or false, depending on whether the client is connected or not. This is one

check that is to be performed before we send the file to the browser.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

System.IO.FileStream f;

long s;

f = new System.IO.FileStream("c:\\inetpub\\wwwroot\\a.html", System.IO.FileMode.Open);

byte[] b = new byte[(int)f.Length];

f.Read(b, 0, (int)f.Length);

Response.Write("<b>Start a.spx</b>");

Response.BinaryWrite(b);

Response.Write("<b>End a.spx</b>");

%>

Output

In the System.IO namespace, there

is a class called FileStream, which has members that can handle file activity.

While creating an object 'f' in the constructor, we state the full path of the

file and also the mode in which the file is to be opened. We then allocate a

byte array, depending upon the size of the file. The file size is acquired

using the property called Length in the FileStream object.

The read function is employed

next, to read the file into the byte buffer. Therefore, the first parameter

specified is 'b'. The second parameter is the starting position in the file,

the position from where the reading should begin. And the last parameter is the

number of bytes to be read, from thereon. As we want to read from the beginning

of the file, and we also want to read the entire file in one go, we specify

zero as the second parameter and the length of the file is the third parameter.

Now that the file is available in

the byte array, the BinaryWriter function is used to add these bytes into a

stream and subsequently, send them to the browser. As the browser receives an

HTML file, it parses through the file and displays the textboxes. The Write

functions before and after the BinaryWrite, work as normal.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write("<b>Start");

Response.ContentType = "Text/plain";

Response.Clear();

Response.Write("<b>End");

%>

Output

<b>End

The Response.ContentType function

initially changes the Content-Type header after writing Start in bold.

Thereafter, the Clear function in Response, clears all HTML output, since its

job is to clear the Buffer. So, the output displayed in the browser is that of

the final Write. Even though the documentation states that headers are reset,

it does not happen in the case of our copy.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write("<b>Start");

Response.ContentType = "Text/plain";

Response.ClearHeaders();

Response.Write("<b>End");

%>

Output

StartEnd

However, the function

ClearHeaders, resets all the headers created in the scriptlet. Thus, the

default Content-type header is sent across, before the contents in the buffer

are handed over to the browser. As a result, we see StartEnd displayed in bold.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write("<b>Start");

Response.End();

Response.Write("<b>End");

%>

Output

Start

The End function states 'enough

is enough', and it sends across the HTML file and the headers immediately.

Thereafter, it closes the connection. Thus, all future output to be sent to the

browser, is conveniently ignored.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write("<b>Start");

Response.Redirect("a1.aspx");

Response.Write("<b>End");

%>

a1.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write("<b>a1.aspx");

%>

Output

a1.aspx

The redirect function merely

stops executing the current file, a.aspx, and starts executing the file to

which it has been redirected. Thus, in case of a Redirect function, any Write

function that follows the Redirect command, is completely ignored. Also, if you

observe the address bar, the URL does not change in the browser. It remaines as

a.aspx.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

Response.Write("a.aspx <br>");

Response.WriteFile("a.html");

%>

The output is similar to one of

the earlier programs. The WriteFile function writes the file contents into the

http stream and sends it to the browser.

Cookies Revisited

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookie c = new HttpCookie("vijay","mukhi");

Response.AppendCookie(c);

%>

One of the simplest things to do

in ASP+, is to send a cookie across. Object 'c' of type HttpCookie is created

by calling the constructor with the name of the cookie vijay, having a value of

mukhi.

Since the cookie option has been

set to prompt in the browser, you will see Alert box for the cookie. Please

note that the constructor does not send the cookie across. It is the function

AppendCookie that does so.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookie c = new HttpCookie("vijay","mukhi");

Response.AppendCookie(c);

HttpCookie c1 = new HttpCookie("vijay1","mukhi1");

Response.AppendCookie(c1);

c = new HttpCookie("vijay1","mukhi2");

Response.AppendCookie(c);

%>

By default, the browser sends a

cookie for the ASP+ session. In the above program, even though three cookies

have been sent, we see only two boxes, since the second and the third cookies

share the same name. Thus, the cookie with the names of vijay1 and value mukhi2

is not sent across separately. The point to be considered here is that you are

free to send as many cookies as you like.

a.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookie c = new HttpCookie("vijay");

c.Values.Add("sonal","wife");

c.Values.Add("zzz","yyy");

Response.AppendCookie(c);

%>

Output

Value in cookie dialog box

sonal=wife&zzz=yyy

a1.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookieCollection cc;

HttpCookie c;

cc = Request.Cookies;

int i = cc.Count;

for (int k = 0; k < i; k++)

{

c = cc[k];

Response.Write("Cookie: " + c.Name + "<br>");

String[] s1 = c.Values.AllKeys;

for (int j = 0; j < s1.Length; j++)

{

Response.Write("Value" + j + ": " + s1[j] + "<br>");

}

}

%>

Output

Cookie: vijay

Value0: sonal

Value1: zzz

Cookie: ASP.NET_SessionId

Value0:

Cookies can be made as complex as

we like. We create one cookie named vijay, and then use the Add function in the

Values property of the cookie, to initialize the subnames and values for the

cookie.

The cookie is transferred as one entity,

with the key-value pairs within it. The different pairs are separated by a

& sign. a1.aspx simply displays all the cookies. For a cookie named vijay,

the last 'for' loop gets executed twice as it holds two values.

a1.aspx

<%@ language="C#" %>

<%

HttpCookieCollection cc;

HttpCookie c;

cc = Request.Cookies;

c = cc["vijay"];

Response.Write("Cookie: " + c.Name + "<br>");

Response.Write(c.Values["sonal"] + "<br>");

Response.Write(c.Values["zzz"]);

%>

Output

Cookie: vijay

wife

yyy

Rewrite a1.aspx with the code

given above. This program first fetches the cookie named vijay and stores it in

'c'. The Values property, which returns a NameValueCollection, has an indexer

that is supplied with the name of the sub key. Consequently, this indexer

returns the value of the sub key.

a.aspx

<html>

Sonal Mukhi

<a href="a1.aspx">Click here</a>

</html>

a1.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

if (!IsPostBack) {

Response.Write(Request.Headers["Referer"]);

ViewState["zzz"] = Request.Headers["Referer"];

}

}

void abc(Object sender, EventArgs E) {

Response.Redirect(ViewState["zzz"].ToString());

}

</script>

<form runat="server">

<input type="submit" OnServerClick="abc" Value="Click" runat="server"/>

</form>

</body>

</html>

Output

Sonal Mukhi Click here

http://localhost/a.aspx

![]()

The file a.aspx has an anchor tag

<a href…> that takes us to page a1.aspx, whenever we click on it.

The ASP+ program a1.aspx displays

a button with the label 'click'. Prior to this, the function Page_Load is

called. This function uses the Request object to access the indexer called

Header. The Header is passed a string called Referer, which informs it about

the file of its origin. As a.aspx was responsible for leading us to a1.aspx

from a.aspx, the URL displays the file name a.aspx.

The WebServer normally keeps a log

of the files that lead a user to its site. This value is then stored in a state

variable called zzz. As we are now aware of the site that brought us to the

current one, by clicking on the button, we can Redirect ourselves to the page

we came from.

Thus, the above code is generic

and goes into a circular loop.

We shall now consider a practical

example to demonstrate the utility of cookies.

a.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

if (Request.Cookies["vijay"] == null)

{

HttpCookie c = new HttpCookie("vijay");

c.Values.Add("Size","8pt");

c.Values.Add("Name","Verdana");

Response.AppendCookie(c);

}

}

public String abc(String k)

{

HttpCookie c = Request.Cookies["vijay"];

if (c != null)

{

if ( k == "FontSize")

return c.Values["Size"];

else

return c.Values["Name"];

}

return "";

}

</script>

<style>

body

{

font: <%=abc("FontSize")%> <%=abc("FontName")%>

}

</style>

Sonal Mukhi

<a href="a1.aspx">Click here</a>

</body>

</html>

a1.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

if (!IsPostBack)

ViewState["zzz"] = Request.Headers["Referer"];

}

void abc(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

HttpCookie c = new HttpCookie("vijay");

c.Values.Add("Size",s1.Value);

c.Values.Add("Name",s2.Value);

Response.AppendCookie(c);

Response.Redirect(ViewState["zzz"].ToString());

}

</script>

<form runat="server">

<select id="s1" runat="server">

<option>8pt</option>

<option>10pt</option>

<option>12pt</option>

<option>44pt</option>

</select>

<select id="s2" runat="server">

<option>verdana</option>

<option>tahoma</option>

<option>arial</option>

<option>times</option>

</select>

<input type="submit" OnServerClick="abc" Value="Click" runat="server"/>

</form>

</body>

</html>

Output

Sonal Mukhi Click here

![]()

Sonal Mukhi

Click here

The above example displays the

text 'Sonal Mukhi' and a hyperlink labelled as 'Click Here'. If we click on the

hyper link, we are transported to a new page called a1.aspx. This page contains two dropdown listboxes

and a button. The first listbox displays the font point size and the second

offers the font face name. By default, the values in these text boxes are 8pt

for the font size and Verdana for the font face name, respectively. At this

stage, if you modify the font size to 12 and the font face name to Tahoma, and

then click on the button, you will be taken back to the original file named

a.aspx. In this file, the text and the Hyperlink will now be displayed in the

newly selected font and size.

Having unravelled the output, let

us now shift the spot-light to the internal working of this program.

The Page_Load function in a.aspx

verifies the existence of a cookie named 'vijay'. Since this page has just been

loaded afresh, the cookie is not available at the moment. This condition

results in true only when the client returns the cookie sent by the server,

while transmitting the user data.

Since the Cookies collection

returns a null, a cookie named 'vijay' is created with two sub keys of Size and

Name. These sub keys are given the values of 8 pt and Verdana, respectively,

which correspond to the font size and the font face name. This cookie is sent

over along with the page generated by a.aspx.

The code enclosed within the

style and /style tags calls the function abc, to adjust the font size and name

as specified by the cookie. Since 'c' has not been currently initialized, the

current text is not displayed in the font and the size specified in the cookie.

Depending upon the value of the parameter 'k', the value of the key Size or

Name, as specified in the Cookie 'Vijay', will be put into service. Thus, the

keys in the cookie named 'Vijay' will decide the format of the text displayed

on the page.

If we click on the hyper-link, it

will result in a call to a1.aspx. By using the Referer parameter in the

Header's Indexer, the name a.aspx of the aspx file is stored in the state

variable named zzz. When the user clicks on the button, the font name and font

size selected by the user, get stored in the listbox ids of s1 and s2

respectively.

This results in a call to the

code in the function abc, where a cookie called 'Vijay' is created. Its sub

keys are initialized to values obtained from the listbox. This cookie is sent

over. Thereafter, using the state variable zzz, we revert back to a.aspx.

In the file a.aspx, since the

cookie 'vijay' now contains specific values, we use these values to set the

font size and the name. As a consequence, the text is displayed in accordance

with the values selected by the user in the listbox, which are now accessible

from the cookie. Thus, we can conclude that the system takes into account the

choices that we make, and each time we load the file a.aspx, the text displayed

on the page is formatted as per the pre-selected font face and size.

This is the mechanism to display

a customized web page. Since by default the page does not retain these values

when the browser is closed, the 'expires' attribute has to be initialized to a

value specified in terms of time or a date. This indicates the duration for

which the cookie is to remain alive. Alternatively, we can store such a value

in DateTime.MaxValue, so that the cookie never expires.

You can verify the retention of

pre-set values between different browser sessions by closing the browser and

re-starting it. The browser would have

retained the settings specified by you earlier.

Cookies are employed to enable

data to persist between the client and the server. A cookie is usually stored

on the Client’s hard disk. In the case of Netscape Navigator, a file called

cookies.txt is created by the browser to store the cookies. The minimum size

per cookie is 4096 bytes.

State Management with Global.asax

a.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

int p1=0;

void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

p1++;

Response.Write("Page_Load() " + p1.ToString() + "<br>");

}

void abc(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Session.Abandon();

//Response.Redirect("a.aspx");

}

</script>

<body>

<form runat="server">

<input type="submit" Value="Refresh" runat="server"/>

<input type="submit" OnServerClick="abc" Value="End Session" runat="server"/>

</form>

</body>

</html>

global.asax

<script language="C#" runat="server">

int r1 =0, r2=0, s1=0,s2=0,a1=0,a2=0;

void Application_Start(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

a1++;

}

void Application_End(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

a2++;

}

void Session_Start(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

s1++;

Response.Write("Session_Start " + s1.ToString()+ "<br>");

}

void Session_End(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

s2++;

Response.Write("Session_End " + s2.ToString()+ "<br>");

}

void Application_BeginRequest (Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

r1++;

Response.Write("Request_Start " + r1.ToString()+ " Application start " + a1.ToString() + "<br>");

}

void Application_EndRequest (Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

r2++;

Response.Write("Request_End "+ r2.ToString()+ " Application end " + a2.ToString() + "<br>");

}

</script>

Output

Request_Start 1 Application start 0

Session_Start 1

Page_Load() 1

![]()

Request_End 1 Application end 0

In the above program, we have

created two files in the directory c:\inetpub\wwwroot. The file a.aspx can be

christened by any name of our choice, but the second file must be named as

global.asax. Prior to loading a.aspx in the browser, ASP.Net checks for the

presence of a file named global.asax. If it exists in the current directory, a

DLL is created with a class called global.asax. This class holds all the code

entered in the asax file. The class resembles the following:

public class global_asax : System.Web.HttpApplication , System.Web.SessionState.IRequiresSessionState {

We discovered this by consciously

committing an error in C#.

There are six functions with pre-defined

names that are added to global.asax. They are:

• Application_Start

• Application_End

• Session_Start

• Session_End

• Application_BeginRequest

• Application_EndRequest

We have also created six

different variables in this special file and initialized all of them to 0. Each

of these six functions increments one variable each by a value of 1. This

signifies the frequency with which the functions get called. A similar action

is repeated in the Page_Load function within the aspx file.

When we load the file a.aspx, it

calls some functions from the file global.asax. But, each of them gets called

only once. The order is as follows: Application_BeginRequest, Session_Start,

Page_Load.

Thereafter, the buttons in the

aspx file are displayed. Lastly, Application_EndRequest is displayed on the

screen.

Please note that there is no

Write function in Application_Start and Application_End, because the Response

object is neither available, nor has it been created so far. By adding a

function, an error is generated, that gives us information about the

global_asax class in the dll.

When we click on Refresh, no code

gets called, because it simply results in a post back to the server.

Output

Request_Start 2 Application start 0

Page_Load() 1

![]()

Request_End 2 Application end 0

The order of calling the various

functions is as follows:

• First, function Application_BeginRequest with variable r1 as 2,

• Then, function Page_Load with variable p1 as 1

• Finally, function Request_End with variable r2 as 2.

The output proves that the

Page_Load function is not called on clicking on the refresh button. Also, no

new session is created. Hence, the Session_Start function is not called.

Now, if you click repeatedly on

the 'End Session' button, you will see the following output:

Output

Request_Start 10 Application start 0

Session_Start 8

Page_Load() 1

![]()

Request_End 10 Application end 0

The Session_Start function is

called once and the Request_Start is called twice.

If we comment out the

Response.Redirect function in the file a.aspx, we obtain the same number of

functions as before, but the Request functions get called only once. What we

are trying to convey here is that, generous amount of code gets called before

and after Page_Load. We can take advantage of these functions and the frequency

of their occurrence to execute certain code at specified intervals.

For the moment, the code in

global.asax does not deal with User Interface calls. These calls handle a much

higher level of event handling, where it deals with application events. We can

create our own events in the form of Application_EventName(signature).

We would also like to clarify

that the file, global.asax, need not be restricted to the wwwroot sub-directory

alone. The only salient feature to be kept in mind is that it should be placed

in the same sub-directory as the aspx file.

The .Net framework creates a

class derived from HttpApplication and places our code in it. Any modifications

made to these files automatically calls for recompiling of the class. We cannot

use a direct URL request to fetch the file, since we are not permitted to view

the code written in it.

If you consider yourself to be a maverick,

you may attempt to do so. But beware, you will then have to deal with the error

number 404.

a.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void abc(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

throw new Exception();

}

</script>

<body>

<form runat="server">

<input type="submit" OnServerClick="abc" Value="Exception" runat="server"/>

</form>

</body>

</html>

Output

![]()

In the above program, An

exception of type System.Exception was thrown. The above program is extremely

simple. It displays a button labelled 'Exception'. If we click on this button,

an exception is thrown.

An exception is a synonym for an

error. The class, when derived from exception, becomes an exception class.

Functions in today's world throw exceptions rather than errors. We get an ugly

yellow coloured screen containing the exception message.

Now, let us endeavour to execute

our own code, whenever an exception is thrown.

We first create a file called

web.config in c:\inetpub\wwwroot as follows:

web.config

<configuration>

<system.web>

<customErrors mode="On" defaultRedirect="a.htm" />

</system.web>

</configuration>

a.htm

hi

This file, which is used to

customize the default workings of ASP.Net, is read each time by the ASP+

framework. By giving the above tags in the file, we can direct the framework to

load a file named a.htm, whenever an error occurs. The URL, however, changes to

the following in the browser address bar:

http://localhost/a.htm?aspxerrorpath=/a.aspx

a.aspx

<%@ Import Namespace="System.Data" %>

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Page_Load(Object Src, EventArgs E )

{

DataView s = (DataView)(Application["sss"]);

s1.InnerHtml = s.Table.TableName;

l.DataSource = s;

l.DataBind();

}

</script>

<body>

<span runat="server" id="s1"/></font>

<ASP:DataGrid id="l" runat="server"/>

</body>

</html>

global.asax

<%@ Import Namespace="System.Data" %>

<%@ Import Namespace="System.IO" %>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Application_Start(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

DataSet d = new DataSet();

FileStream f = new FileStream(Server.MapPath("s.xml"),FileMode.Open,FileAccess.Read);

StreamReader r = new StreamReader(f);

d.ReadXml(r);

f.Close();

DataView v = new DataView(d.Tables[0]);

Application["sss"] = v;

}

</script>

s.xml

<root>

<schema id="DocumentElement" targetNamespace="" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" xmlns:xdo="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:xml-xdo" xdo:DataSetName="DocumentElement">

<element name="Products">

<complexType>

<all>

<element name="ProductID" type="int"></element>

<element name="CategoryID" minOccurs="0" type="int"></element>

</all>

</complexType>

</element>

</schema>

<DocumentElement>

<Products>

<ProductID>2002</ProductID>

<CategoryID>2</CategoryID>

</Products>

<Products>

<ProductID>2003</ProductID>

<CategoryID>2</CategoryID>

</Products>

</DocumentElement>

</root>

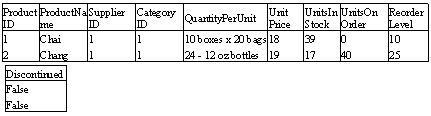

Output

Products

In the file a.aspx, we begin with

the assumption that a DataView object has already been created. Then, we

initialize a span member named InnerHtml to a Table name that is picked up from

the DataView.

This explains the display of

Products in the browser window. Then, the DataSource property of the DataGrid

named l, is initialized to the DataView object named 's'.

Finally, the function DataBind display the records in a Tabular format.

Now, let us cover up the

loopholes in the explanation of the above program.

In the global.asax file, we have

added adequate amount of code in the Application_Start function. A DataSet

object named 'd' is created to hold the data. Also, a FileStream object named

'f' is given a reference to an XML file named s.xml, which is opened for

reading purpose only. The file s.xml resides in the same directory. The

StreamReader object named 'r' is given the FileStream parameter in its

constructor, to enable it to read this file. d.Readxml will finally read the

contents of the xml file in its dataset. We are not going into the explanation

of s.xml, since it remains the same as

before.

After closing the file, a

DataView object 'v' is created. Application variables are similar to State

variables, in the sense that, they are valid only while the application is on.

The Application is an indexer. Hence, we provide a string named 'sss' to hold

the DataView object. The variable 'sss' is now an Application variable.

The Application variable sss,

containing the DataView object, is used in the Page_Load function. It supplies

the data contained in the DataSet. The functions Page_Load and

Application_Start are called only once, i.e. when the page is initially loaded.

Both perform one-time actions. Thus, all resource intensive actions, such as,

initializing the DataView, which is a one-time effort, are placed in this

function.

There can always be a situation

where multiple threads would like to access both, an application and its

objects, concurrently. So, the data that does not change very often, must be

stored with an Application scope. Data that needs to be initialized just once

and then it is required to be only read, is an ideal example of such data.

In the above example, only the

first request is resource intensive, and will incur a performance overhead

while creating the DataView. All the other requests will be executed at

lightning speed.

Sessions

a.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

String abc(String k)

{

return Session[k].ToString();

}

</script>

<style>

body

{

font: <%=abc("Size")%> <%=abc("Name")%>

}

</style>

Sonal Mukhi

<a href="a1.aspx">Click here</a>

</body>

</html>

a1.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

if (!Page.IsPostBack)

ViewState["zzz"] = Request.Headers["Referer"];

}

void abc(Object sender, EventArgs E)

{

Session["Size"] = s1.Value;

Session["Name"] = s2.Value;

Response.Redirect(ViewState["zzz"].ToString());

}

</script>

<body>

<form runat="server">

<select id="s1" runat="server">

<option>8pt</option>

<option>10pt</option>

<option>12pt</option>

<option>44pt</option>

</select>

<select id="s2" runat="server">

<option>verdana</option>

<option>tahoma</option>

<option>arial</option>

<option>times</option>

</select>

<input type="submit" OnServerClick="abc" Value="Click" runat="server"/>

</form>

</body>

</html>

global.asax

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Session_Start(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Session["Size"] = "8pt";

Session["Name"] = "verdana";

}

</script>

The above example conducts itself

in the same manner as the earlier Cookies' example. However, this one is much

simpler. It is next to impossible for the user to detect the method used to

obtain the above output by merely looking at the end result.

Let us start with the file named

a.aspx.

The code in a.aspx remains the

same, except for modifications made in the function abc. The Session indexer is

used to retrieve the value of a variable that is created in the global.asax

file. In the global.asax file, we have created two variables named Size and

Name to store the font size and the font name respectively. You may have

noticed that this code is placed in the function named Session_Start.

When we click on the button in

the file a1.aspx, the Sessions variables get re-initialized with the values

selected in the listboxes. Thereafter, there is a redirection to the original

page named a.aspx.

If we replace Cookies with

Session, the entire picture would be more transparent and lucid.

We can configure the state of the

session object by using the sessionstate section in the file named web.config.

Adding the line <sessionState timeout="40" /> will increase the

default timeout from 20 minutes to 40 minutes. The timeout parameter ends the

session either in 40 minutes or when you close the browser, whichever occurs

first.

We now add the following line to

the file named web.config

web.config

<configuration>

<system.web>

<sessionState cookieless="true" />

</system.web>

</configuration>

We have selected the cookie

option named 'prompt', and in config.web, we have disallowed the use of a cookie

to keep track of sessions. Thus, the web server has no choice but to use the

URL to keep track of sessions. As a result, the new URL looks like the

following:

http://localhost/(ybp3byicimzjix3s0veyjb55)/a.aspx

This method is termed as URL

rewriting.

ViewState

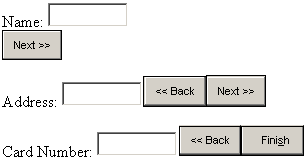

The illustration given below may

be a large program, but it is deceptively simple to understand.

a.aspx

<html>

<script language="C#" runat="server">

void Page_Load(Object Src, EventArgs E )

{

if (!IsPostBack)

ViewState["zzz"] = 0;

}

void a1(Object Src, EventArgs E )

{

String pid = "P" + ViewState["zzz"].ToString();

ViewState["zzz"] = (int)ViewState["zzz"] + 1;

String Id = "P" + ViewState["zzz"].ToString();

Panel p = (Panel)FindControl(Id);

p.Visible=true;

p = (Panel)FindControl(pid);

p.Visible=false;

}

void a2(Object Src, EventArgs E )

{

String Id = "P" + ViewState["zzz"].ToString();

ViewState["zzz"] = (int)ViewState["zzz"] - 1;

String pid = "P" + ViewState["zzz"].ToString();

Panel p = (Panel)FindControl(Id);

p.Visible=false;

p = (Panel)FindControl(pid);

p.Visible=true;

}

void a3(Object Src, EventArgs E )

{

String s = "P" + ViewState["zzz"].ToString();

Panel p = (Panel)FindControl(s);

p.Visible=false;

l.Text += "Name: " + na.Value + "<br>";

l.Text += "Address: " + a.Value + "<br>";

l.Text += "Card : " + n.Value + "<br>";

}

</script>

<body">

<form runat="server">

<ASP:Panel id="P0" Visible="true" runat="server">

Name:

<input id="na" type="text" runat="server">

<br>

<input type="submit" Value=" Next >> " OnServerClick="a1" runat="server">

</ASP:Panel>

<ASP:Panel id="P1" Visible="false" runat="server">

Address:

<input id="a" type="text" runat="server">

<input type="submit" Value=" << Back " OnServerClick="a2" runat="server">